PRIDE in the Past: A Photo Essay

The well-known initialism LGBT has only been in common use since the late 20th century, and has undergone various transformations since then, but members of that community have always existed (you just probably weren’t taught about them growing up). In honour of Pride 2022, we’re taking a look back at some international trailblazing women of the LGBTQIA+ community.

(Content Warning: Some of the following biographies contain instances of homophobia, transphobia, Nazism, drug and alcohol abuse, and physical and child abuse which may be hurtful to some readers).

You can scroll down through all of the biographies at your own pace, or, to get quickly to one of them, click on their name below:

Ladies of Llangollen The Sewing Circle

Lucy Hicks Anderson Ernestine Eckstein

Sappho

(c.620BC - c.570BC)

‘Like the sweet apple that reddens upon the topmost bough,

Atop the topmost twig, - which the pluckers forgot, somehow, -

Forget it not, nay; but got it not, for none could get it till now.’

Sappho and Erinna by Simeon Solomon, 1864

Sappho was an Archaic Greek poet from the island of Lesbos who today is revered as a feminist lesbian icon, with the words sapphic and lesbian inspired by her name and home island. Born in c. 620 BC Sappho frequently professed a love and desire for women in her poems, which were so popular that she had coins made in her honour and many ancient texts declared her the ‘Tenth Muse.’ Unfortunately, extremely little is known about her life now and her sexuality has been debated (and suppressed) for millennia. Very little of her work has survived, and while most was likely lost through time and a failure to write it down, there are legends that say some of her poems were ‘purposefully destroyed by the medieval church to suppress lesbian love poetry’ and there is some evidence to suggest that Pope Gregory VII ordered her works burned (c. 1073CE) for this very reason. Regardless of the attempt to suppress her voice, Sappho remains ‘a figurehead of lesbian iconography’ today.

Ladies of Llangollen:

Eleanor Butler & Sarah Ponsonby

(1739 - 1829) (1755 - 1831)

In 1778, Eleanor Charlotte Butler (b. 1739) and Sarah Ponsonby (b. 1755) ran away together. They had met ten years prior in Kilkenny, Ireland and had formed a close ‘intense’ relationship very soon after. By 1778 they faced a crisis. Eleanor, now 40 and unmarried, was perhaps going to be placed in a convent by her family and Sarah’s family were attempting to marry her off. She declared that she planned to ‘live and die with Miss Butler’ and in their first attempt at elopement, she allegedly ‘leapt out of a window, in male attire, armed with a pistol and her small dog, Frisk.’ Their families found them and forced them apart, but this did not deter them, and another attempt a few months later was a success. They renovated a small cottage they called Plas Newydd in Wales with their maid Mary Caryll (who had escaped with them) and settled into what they called ‘exquisite retirement.’ They enjoyed working on their estate, studying, and hosting friends together.

Plas Newydd today

Their situation was the subject of fascination to many at the time, and visitors to Plas Newydd included William Wordsworth, Charles Darwin and Anne Lister. They were inundated with so many visitors, in fact, that Eleanor once lamented in her diary ‘when shall we ever be alone together?’ Of course, the nature of their relationship has been debated for centuries. Prince Puckler-Mukau – a contemporary of the couple - is known to have said of them that they were ‘certainly the most celebrated [virgins] in Europe’ while others called them ‘damned sapphists.’ More recently, Prof. Fiona Brideoake of American University in Washington DC has suggested that queer would be a more appropriate label than the specific label of lesbian, ‘particularly as queerness is a broad concept and significantly defined by its difference from typicality.’

Eleanor and Sarah lived together with a successive line of dogs they named Sappho – rarely ever leaving Plas Newyyd – until the day they died (Eleanor in 1829 and Sarah two years later in 1831). They were buried together with their maid, Mary.

Anne Lister

(1791 - 1840)

“I love and only love the fairer sex and thus beloved by them in turn, my heart revolts from any other love than theirs.”

Anne Lister by Joshua Horner, 1830

Born in 1791, Anne Lister was a prolific diarist and wrote religiously between 1806 and her death in 1840. Known also as ‘Gentleman Jack,’ she was a charismatic and ‘phenomenally intelligent’ woman who inherited her uncle’s estate – Shibden Hall – after his death in 1826. As a wealthy landowner, she remained, disappointingly but unsurprisingly, "interested in defending the privileges of the land-owning aristocracy." An astute businesswoman, entrepreneur, and traveller, Anne lived life to the beat of her own drum. She had relationships with women from when she met her first love, Eliza, at boarding school as a young teenager. It was with her that Anne developed a code in which to write the most intimate details of her life in in her journals. Mariana Belcombe, however, was who became her life’s love. For years, the couple travelled about 40-miles to see each other and wrote to each other constantly. But in 1815, Mariana married a widower which broke Anne’s heart.

‘Surely no-one ever doted on another as I did then on her.’

After a year apart, they reignited their affair. Anne wrote, ‘Sat up lovemaking. She [asked me to swear] to be faithful, to consider myself as married. I shall now begin to think and act [as] if she were my wife.’ It wasn’t to last though as Mariana grew increasingly fearful that their relationship would be found out, and by 1823 the affair was over for good.

Anne Lister 1822, probably by a Mrs Taylor

After some time spent travelling, Anne met Ann Walker and in 1834 they ‘took communion together’ in a church and exchanged rings, after which they considered themselves married. Ann moved into Shibden Hall, and they lived there until Anne’s early death, aged 49 in 1840.

While providing important detailed accounts of social, political, and economic events of the time, Anne’s diaries also contain a great deal about her lesbian identity and relationships she had with women. For this reason, they were kept hidden (and almost burned) by a descendant who was afraid that should her relationships be made public it would ruin his family’s name. Thankfully, the journals were later found and then uncoded in the 1980s by Helena Whitbread. In the end, it was Anne’s ‘comprehensive and painfully honest account of lesbian life and reflections on her nature’ that was deemed so important in 2011 that her diaries were added to the register of the UNESCO Memory of the World Programme.

Lucy Hicks Anderson

(1886 - 1954)

Lucy Hicks Anderson (nee Lawson)

TW: Transphobia

Born in 1886 in Kentucky, USA, Lucy insisted on wearing dresses to school as a child, so her mother took her to a doctor who told her that she should allow Lucy to live as a female. By 1901, aged 15, she left home and worked as a domestic servant before moving to Texas, and eventually, to New Mexico where she married her first husband, Clarence Hicks in 1920. Together they moved to California where Lucy became a very popular member of the community and was known as a nanny, skilled chef and a talented socialite who hosted the best parties. Eventually, Lucy saved up enough money (and made enough connections in town) to open a brothel and speakeasy. Her parties were so good, in fact, that on one particular occasion when she was arrested for selling liquor in prohibition America, ‘Charles Donlon, the town’s leading banker, promptly bailed her out [because] he had scheduled a huge dinner party which would have collapsed dismally with Lucy in jail.’

Lucy with some local children c. 1940s. Source: Oxnard: 1941-2004.

In 1929, Lucy divorced her husband and in 1944 she married retired soldier, Reuben Anderson. All seemed to be going well until the following year when ‘an outbreak of venereal disease in the Navy was traced back to Anderson’s brothel.’ All of the women employed there, including Lucy, were examined by the doctor who then went public with what he found out about 59-year-old Lucy. Upon this discovery, the local District Attorney voided Lucy’s marriage to Reuben and arrested her for ‘perjury’ on her marriage license. During the trial, Lucy strongly defended herself by stating:

“I defy any doctor in the world to prove that I am not a woman. I have lived, dressed, and acted just what I am—a woman.”

Lucy and her husband were convicted and sentenced with jail time and were both then further charged with fraud when they concluded that Lucy had been ‘illegally receiving Anderson’s allotment checks as the wife of a member of the U.S. Army.’ They were both sent to a men’s prison where Lucy was banned by court order from wearing women’s clothing. When they were finally released from jail, they were prohibited from moving back to the town they had lived before, and so they relocated to Los Angeles where Lucy died in 1954.

Dora Richter

(1891 - 1933?)

Dora Richter

TW: Transphobia, Nazism, Homophobia

In 1931, Dora Richter became the first known person to undergo gender confirmation surgery under the care of sex-research pioneer Magnus Hirschfeld in Berlin.

Born into a poor German family in 1891, Dora always identified as a woman. When she was a little older, because it was extremely hard (if not impossible) to find work as a trans woman, she used to dress in what was regarded as male clothes and work as a waiter during the summer under her birth name while spending the remainder of the year living as the woman she was. This wasn’t exactly easy though, and she was arrested and imprisoned on a handful of occasions for ‘cross-dressing.’

Eventually, she was released into the care of Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld at Berlin’s new Institute for Sexual Science where she was able to obtain genital reconstruction surgery, including a vaginoplasty when she was 40, making her the first known trans woman to do so. To pay her way, she worked as a housekeeper within the Institute alongside other trans women and according to some sources, she liked to knit, sew and sing ‘old folk-songs.’

Two Women Dancing (1928) by Jeanne Mammen, Berlin

The Institute had been opened in 1919 by Dr. Hirschfield and his collaborators and as well as having the medical division that Dora would have visited, it also housed a research library and a vast archive reputed to have been ‘the world’s first repository of LGBTIQ history.’ Berlin, at this time, was ‘a haven and refuge for gays and lesbians from all over the world’ boasting ‘170 clubs, bars and pubs for gays and lesbians, as well as riotous nightlife, […] a gay neighbourhood’ and political parties that were being set up to advocate for equal rights.

Students of the Deutsche Studentenschaft, organized by the Nazi party, parade in front of the Institute for Sexual Research

Horrifically though, by 1933 the Nazi Party had basically obtained absolute control of the country, and almost immediately began its ‘purge’ of gay clubs in Berlin, forbade sex publications, and banned organised gay groups. In May, a group of fanatical right-wing students attacked the Institute, and the state authorities then burned the library and archives publicly on the streets, erasing years of LGBTQIA+ research and history. Extensive lists containing names and addresses were seized and it is believed that these were later used by the Nazis to round-up, imprison, and murder gay people – specifically gay men. Sadly, there is no record of Dora after this attack, and it is widely assumed that she was killed during, or shortly thereafter it, with at least one source stating that she was beaten to death inside the Institute where she had lived happily for so many years.

German students and Nazi SA members plunder the library of the Institute

Dora had lived her life showing incredible perseverance and determination in the face of extreme adversity and while she is still not nearly as recognised as she should be today, to those who do know her story, she is considered a true role model.

Dorothy ‘Dolly’ Wilde

(1895 - 1941)

Dolly Wilde

In 1895, the famous Irish playwright, Oscar Wilde, was sentenced to prison for the crime of ‘gross indecency’ (AKA consensual homosexual relations. Same-sex sexual activity was illegal in Ireland until 1993!). Three months into his imprisonment, his niece Dorothy ‘Dolly’ Wilde was born in London.

Dolly Wilde

Although she would never meet Oscar, who died in 1900, she idolised him and anyone who knew the two of them remarked how alike they were, both in appearance and personality. Dolly never talked much about her childhood, so little is known, but as a teen during WWI, she went to France to drive an ambulance where she began a relationship with her fellow ambulance driver Marion ‘Joe’ Carstairs.

Natalie Clifford Barney

After the war, she remained in Paris and became a frequenter of private parties and literary circles. She was known for her ‘quick wit [and] charming conversation,’ and was a great addition to any gathering. She was known to many as a talented storyteller, but unfortunately, she never took advantage of this by writing anything down. Much like Oscar used to do, Dolly spent this time ‘liv[ing] out of her suitcase moving between hotels, borrow[ing] apartments and the spare rooms of her well-off friends.’ Even though she enjoyed garnering the attention of men, Dolly was only interested in pursuing women, and in 1927 she began a long relationship with openly lesbian American playwright, poet and novelist, Natalie Clifford Barney.

Dolly Wilde, c. 1925

Distressingly for Dolly, while her relationship with Natalie continued right up until her death, Natalie was simultaneously having relationships with other women. Dolly was also an alcoholic and drug-addict and even though she tried to get clean on a few occasions, none were successful. In 1939, she was diagnosed with breast cancer, for which she refused treatment, opting instead for alternative therapies, and sadly she died in 1941, aged 45.

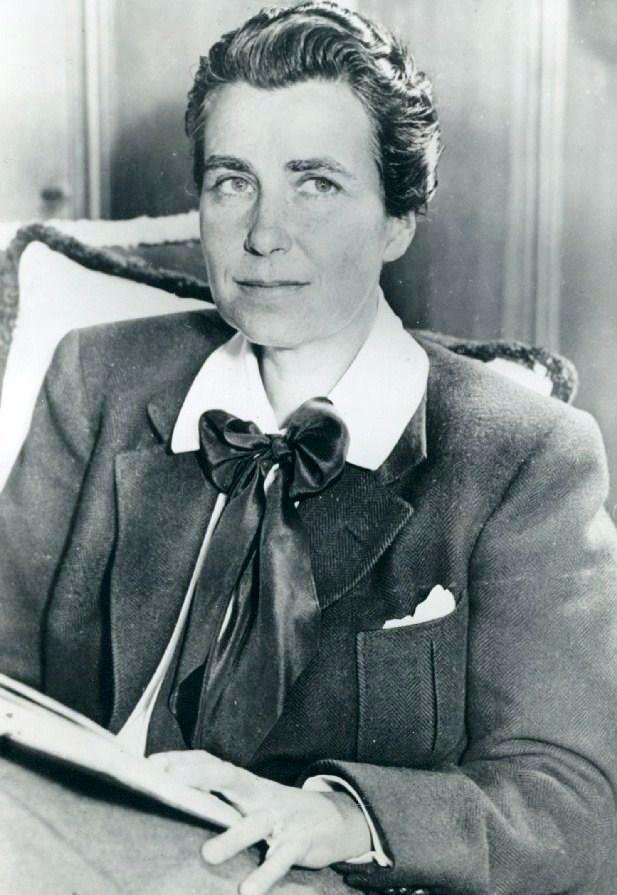

Dorothy Arzner

(1897 - 1979)

Dorothy Arzner

Born in 1897, Dorothy Arzner was the only female director working in Hollywood from the late 1920s until her retirement in 1943. Her film career began after WWI in 1919 when she took a job in the script department and within a few months she became an editor, eventually rising up the ranks to edit films for Paramount studios. By 1927, Dorothy ‘had an offer to write and direct a film for Columbia’ which appealed massively to her, as she had known from her first week on the job back in 1919 that ‘if one was going to be in this movie business, one should be a director because he was the one who told everyone else what to do.’ She threatened to leave Paramount and when she was made an offer to discuss directing sometime in the future, Dorothy responded that she’d ‘rather do a picture for a small company and have my own way than a B picture for Paramount.’ Walter Wagner, head of Paramount’s New York studio then offered her the chance to direct a comedy which was later titled Fashions for Women (1927). This was Dorothy’s directorial debut, and it was a commercial success, so Paramount hired her for a string of more silent movies and in 1928 she became the first woman to direct a sound film – Manhattan Cocktail.

Dorothy Arzner on set

The following year, in 1929, Dorothy directed Paramount’s first ever talkie feature film The Wild Party. It starred Clara Bow in her first talking picture and when she found it awkward to act and move about the set due to the sound equipment, Dorothy had a microphone put at the end of a fishing rod to allow her leading lady to move about freely. Yes, Dorothy invented the first ever boom mic!

Dorothy Arzner

After she directed a few more features for Paramount, Dorothy went freelance and made some of her most well-known, well-received movies starring Katharine Hepburn (Christopher Strong, 1933), Rosalind Russell (Craig's Wife, 1936); Joan Crawford (The Bride Wore Red, 1937) and Lucille Ball and Maureen O’Hara (Dance, Girl, Dance, 1940). Dorothy’s movies often gave actresses of the time ‘intelligent, complex roles centring around moral dilemmas and a cynical attitude to marriage’ and ‘independent, strong-willed female protagonists whose decisions reflect a conflict with stereotypes.’

Dorothy retired from filmmaking in 1943 and founded the first class on filmmaking at the Pasadena (California) Playhouse (Francis Ford Coppola was one of her students!) She directed over 50 Pepsi ads throughout the 1950s at the request of her friend Joan Crawford and in 1976 she was honoured by the Directors Guild of America (of which she was the first female member).

Dorothy (left) and Marion

While she liked to keep her private life private, Dorothy never exactly hid the fact that she was a lesbian. She had a 40-year relationship with choreographer Marion Morgan which began about the time she made her directorial debut in 1927. The couple worked together on a handful of Dorothy’s films, with Marion choreographing some of the scenes in Fashions for Women (1927), Get Your Man (1927) and Manhattan Cocktail (1928). They lived together in Hollywood from 1930 until Marion’s death in 1971. Dorothy died in 1979, aged 82.

The Sewing Circle

(1920s - 1950s)

From the very early days of cinema, any portrayal of same-sex relationships was expressly forbidden, but this didn’t mean that Hollywood wasn’t populated with gay people. Many of the most famous women in Hollywood during the Golden Age (1920s-50s) were queer; actresses like Greta Garbo, Joan Crawford, Marlene Dietrich, Tallulah Bankhead and Katharine Hepburn, and others in the creative industry like poet and playwright Mercedes de Acosta, and director Dorothy Arzner, were all members of an informal network of lesbian and bisexual women, known as the Sewing Circle. It isn’t certain where the term originated, although many attribute it to Russian American actress, director, and producer Alla Nazimova (godmother of US First Lady Nancy Reagan) who had confirmed romantic relationships with Mercedes, Dorothy, and Dolly Wilde.

Alla Nazimova, 1913

Secrecy and privacy were of the utmost importance to most members. These women were working in an industry that sought to silence them, in a society that for the most part believed that women-loving-women were ‘neurotic, tragic, and absurd,’ under a government that actively suppressed them. Things became even more difficult for gay people in America from 1938 on with the introduction of the Committee on Un-American Activities, established ‘to investigate alleged disloyalty and rebel activities on the part of private citizens, public employees and organizations suspected of having Communist ties.’ Known as the Lavender Scare, gay men and women were dubbed ‘national security risks’ because it was believed that they would be more susceptible to manipulation and blackmail. This is the context in which the Sewing Circle was set.

Pat ‘Dubby’ Walker

(1938 - 1999)

“‘Most of us had two strikes against us as lesbians and as women. She was discriminated against on four counts – because she was also blind and an African American.’ ”

Pat Walker

Pat Walker (nicknamed Dubby because she was short) was born in 1938, America. Growing up Black, female, blind, and a lesbian at this time may seem like it would have been incredibly hard, and no doubt it was at times, but luckily, she had a very supportive family. Speaking in the 1980s she recalled, ‘when I was eleven or twelve, my mother told me about gayness. [She] had gay friends and my sister is also gay. At fourteen I realized I liked girls. I never felt bad about myself because of it.’

Independence was very important to Pat who spent a year at an independent living centre ‘learning how to survive, how to use a cane, and how to use her other senses to ‘see’ her way on downtown traffic-filled seats.’ To support herself financially, Pat worked at a telephone wake-up service and then operated a shop in the lobby of an office building.

It wasn’t until 1958 that she heard about the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB). Founded in 1955, DOB was the first lesbian civil and political rights organisation in the US. The priorities of some of the original members included: having a place where they could dance (because dancing with someone of the same sex was illegal in public spaces), providing a social alternative to lesbian bars (which were subject to raids) and privacy (from parents, families and ‘gaping tourists in the bars’). Whilst visiting Oakland’s Orientation Centre for the Blind, one of the co-founders of DOB, Billye Talmadge, met Pat and immediately ‘picked [her] out as gay.’ Billye began taking Pat to various meetings, picnics and get-togethers and had Pat work with her on The Ladder, a magazine published monthly by the DOB.

Eventually, Pat was elected President of the San Francisco chapter of the DOB and ‘proved to be a strong leader who had no trouble delegating authority.’ She was one of the representatives of the DOB present at a retreat in 1964 that saw the coming together of lesbian and gay leaders as well as fifteen clergymen for a discussion on ‘The Church and the Homosexual.’ Those present spent a few days together ‘breaking down stereotypes.’ As well as this role, she volunteered her time answering a night helpline set up by San Francisco’s Suicide Prevention Agency.

In her later life, Pat moved into a house in the desert with her dog and two cockatiels where she could play her instruments (she played the saxophone, piano, flute, piccolo, and guitar) as loudly as she wanted. She died in 1999, ‘surrounded by friends and family, who prompted the hospice volunteer to observe, “You are all so different. She must have been quite a person.”’ Writing about her a few years later, Del Martin – co-founder of DOB – wrote that ‘with her humour, her sensitivity and warmth, her caring and patience with people, and her funny stories’ Pat was an immensely popular character within every circle she had moved in.

Ernestine Eckstein

(1941 - 1992)

This photo, taken in October 1965 of a picket line in front of the White House and organised by Frank Kameny, founder of the Mattachine Society of Washington DC was one of the first times gay people had organized to come together and publicly demand their rights in America. The only person of colour in attendance was Ernestine Eckstein. Her sign read: Denial of Equality of Opportunity is Immoral

Though known as Ernestine Eckstein now and throughout her activism, she was born Ernestine Delois Eppenger in 1941 in Indiana (the change of name came as a way to protect herself from being outed in her hometown and fired from her job). Her involvement in political activism began when she attended college in Indiana and became a NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People) chapter officer, although extremely little is known about her involvement at this time. Following her graduation in 1963, she moved to New York City. She met up with a friend from college who informed her then that he was gay. While she had ‘been attracted to various teachers and girlfriends’ before, she said:

“I had never known about homosexuality, I’d never thought about it. It’s funny because I’d always had a very strong attraction to women. But I’d never known anyone who was homosexual […] I didn’t know there were other people who felt the way I did.”

Her friend explained to her what gay meant and ‘then all of a sudden, things began to click. Because at that time I was sort of attracted to my roommate, and I thought: am I sexually as well as emotionally attracted to her? And it dawned on me that I was […] I went through the soul-searching for several months […] the next thing on the agenda was to find a way of being in the homosexual movement – because I assumed there was such a movement…’

Some members of the Daughters of Bilitis c. 1956

Ernestine had experience in the Civil Rights movement and had expected to find a similar one pertaining to gay people – but at this time, in the early 1960s, there wasn’t so much of a gay movement as what there is today, and what she did find were many debates around the direction any such movement should go in. Many of the older generation were still trying to gain rights by negotiating with doctors and psychologists (who believed homosexuality was a mental illness) while younger activists wanted to take the issue to the people and to government officials. Ernestine became one of the earliest advocates of the latter, saying in 1966 that ‘any movement needs a certain number of courageous people […] They have to come out on behalf of the cause and accept whatever consequences come. Most lesbians that I know endorse homophile picketing but will not picket themselves...’

Ernestine was the first black woman to feature on the cover of The Ladder, a magazine run by the DOB. The photo was purposefully taken from the side so as she wouldn’t be overly recognisable (and outed)

Ernestine became the Vice President of the New York chapter of the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB) in 1964. By this time time, the wider debate of which direction the ‘homophile’ movement should go in was happening within the organisation too.

Frank Kameny marching in the first Pride parade in 1970, holding a sign with the slogan he coined ‘Gay is Good.’

Some members of the DOB, such as Ernestine, were inspired and influenced by the success of the Civil Rights movement and tried to move the lesbian and gay struggle for equality in the same way. In 1965, Ernestine began to reach out to Frank Kameny – one of the most significant figures in the gay rights movement in the US, co-founder of the Mattachine Society of Washington (one of the earliest national gay rights organisations in the country), and creator of the slogan ‘gay is good’ – with the idea of having him speak at an event organised by the NY DOB. Writing to him in early 1966, she said, ‘I want you to be free enough to say whatever you want, so to speak – about any aspect of the movement. Keep in mind my particular aim: to get these people to realize there is such a thing as the homophile movement and possibly begin to develop a fuller concept of themselves as part of it.’ Just a few days later, however, she had to write to inform him that the DOB had decided to uninvite him. This was probably because some within the DOB disliked Frank and disliked the fact that a man was telling them what to do, while others were simply put off by the idea of social action.

Towards the end of the 1960s, Ernestine left the DOB (which eventually fell apart in 1972) and moved west to California. It is alleged that she left because she had ‘gotten tired of all the political wrangling and disagreements within DOB over strategies and tactics.’ In California she joined the radical, activist group Black Women Organized for Action (BWOA), founded in 1973 ‘in response to the lack of representation of Black women in local women's organising.’ There is hardly any record of Ernestine after this, however. She died in 1992 – although her cause of death is not publicly known.

Ernestine was undoubtedly one of the most progressive thinkers of her time within the gay liberation movement. In 1965 she said she’d ‘like to find a way of getting all classes of homosexuals involved together in the movement’ (including trans people) and was resolute in that ‘the homosexual has to call attention to the fact that he’s been unjustly acted upon. This is what the Negro did.’ Journalist, Eric Marcus, said it best when he said of Ernestine: ‘She was a visionary. She anticipated, predicted, and foreshadowed so many of the issues that would face the LGBTQ community in the decades to come.’

Marsha P. Johnson & Sylvia Rivera

(1945 - 1992) (1951 - 2002)

Marsha P. Johnson

TW: Transphobia, Homophobia, Child Abuse

Marsha P. Johnson was born in 1945 in New Jersey, the fifth of seven children, and from a very early age she felt most comfortable in clothes made for girls. After graduating high school in 1963 and a brief stint in the Navy, she moved to New York City ‘with only $15 and a bag of clothes.’ Here, she was able to dress almost exclusively in the clothes she wanted and began going by the name Marsha P. Johnson (the P stood for her life motto ‘pay it no mind!’)

At the time, Marsha went by she/her pronouns and described herself as ‘a gay person, a transvestite, and a drag queen’ but most people today (including her friends) say that if she were still alive, she would probably consider herself a trans woman, a term that was not commonly used in Marsha’s time.

Sylvia Rivera

Shortly after arriving in the big city, Marsha met Sylvia Rivera – a Puerto Rican, New York-born trans girl six years her junior. Sylvia was an orphan who had been homeless from the age of 11 and was being exploited as a ‘child prostitute’ until a group of drag queens took her under their wing. The pair became instant friends and Marsha taught Sylvia everything she knew about make-up and living on the streets. Eventually, to make money, they ‘hustled’ which meant working as sex workers, but this was an incredibly dangerous profession in 1960s New York, particularly for people like Marsha and Sylvia, and they faced violence and the threat of arrest every single day. Despite their difficult day-to-day life, they made the most of what they had and were known for their charismatic and fun-loving personalities.

The only known photo from the first night of the Stonewall riots

Then, in the early hours of 28 June 1969, the ‘most significant event in the history of the gay liberation movement and the catalyst for the modern fight for LGBTQ rights’ – the Stonewall riots – began, when police raided the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village. When the police became violent, people who had been in Stonewall and other lesbian and gay bars in the area, fought back, and this continued over a few days. Marsha was there on the first night and is widely regarded now as one of the initial instigators, although she herself refuted this.

“I didn’t get downtown until about two o’clock […] the place was already on fire. And it was a raid already. The riots had already started. And they said the police went in there and set the place on fire.”

There are conflicting reports about Marsha’s role at Stonewall that night, but whatever the details, she was there on the frontlines, standing up for herself and for the LGBTQIA+ community at large. In fact, drag queens and trans women – who were often overlooked and turned away by other members of the community - were at the forefront of the uprising.

Sylvia and Marsha at a gay rights protest in 1973

Following the Stonewall riots, Marsha and Sylvia attended many demonstrations, sit-ins, and meetings but still, they felt excluded within the community even though trans people were more likely to face abuse, police brutality and homelessness. So, in 1970, they set up STAR (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries), a place where homeless queer youth could live in relative safety with each other. It was a ‘slum building’ with few amenities, but it was all they could afford.

“When we asked the community to help us there was nobody […] We were nothing! We were taking care of kids that were younger than us. Marsha and I were young, and we were taking care of them […] We tried. We really did […] We went out and made money off the streets to keep those kids off the streets. We already went through it. We wanted to protect them. To show them that there was a better life.”

Marsha and Sylvia at a protest in 1973

Marsha and Sylvia c1989/90

STAR was shut down after about two years because there was no money to support it. In the mid-70s, Sylvia moved upstate with her partner while Marsha remained in the city and performed in drag shows. In 1980 she moved in with a friend and when that friend’s partner became terminally ill with AIDS, Marsha looked after him. She became a frequent visitor to those ill with AIDS in hospitals and spent hours sitting with them. She herself contracted the virus in 1990. Two years later, shortly after the gay pride parade of 1992, Marsha’s body was found in the Hudson River. Her death was ruled a suicide but her friends, including Sylvia who moved back to New York, were convinced that she had been the victim of a hate crime as there was a large gash to the back of her head. In 2002 her death was reclassified as ‘undetermined.’

The 1990s were a difficult period for Sylvia but in 2001 she resurrected STAR as an active political organisation and campaigned for the New York City Transgender Rights Bill and for a trans-inclusive New York State Sexual Orientation Non-Discrimination Act. Sadly, she died in 2002 of liver cancer, aged just 50.

Leslie Feinberg

(1949 - 2014)

“…an anti-racist white, working-class, secular Jewish, transgender, lesbian, female, revolutionary communist.”

Leslie Feinberg

TW: Transphobia, Homophobia

In about 1963, aged 14, Leslie Feinberg dropped out of school and soon after became estranged from her family. She had been ‘mercilessly abused and discriminated against for being gender variant and non-conforming.’ Biologically a woman, but male presenting, she would later explain:

“I am female-bodied, I am a butch lesbian, a transgender lesbian — referring to me as ‘she/her’ is appropriate, particularly in a non-trans setting in which referring to me as ‘he’ would appear to resolve the social contradiction between my birth sex and gender expression and render my transgender expression invisible. […] I like the gender-neutral pronoun ‘ze/hir’ because it makes it impossible to hold on to gender/sex/sexuality assumptions about a person you’re about to meet or you’ve just met. And in an all trans setting, referring to me as ‘he/him’ honors my gender expression in the same way that referring to my sister drag queens as ‘she/her’ does.”

Leslie. Credit: Bill Hackwell

Feinberg spent hir early life working low-paying jobs as well as pursuing many causes as an activist and by her early 20s she became a member of the Workers World Party - a revolutionary Marxist–Leninist political party in the US that ‘supports the struggles of all oppressed peoples.’ Leslie worked extensively as editor and columnist for the organisation’s newspaper and is considered the first theorist to have advanced a Marxist concept of transgender liberation – which ‘understands the oppression of trans people as not just the result of individual people’s prejudice, but as a part of capitalist exploitation.’

Cover Image: Alyson Books

Leslie later moved to New York where ze became involved in confronting oppression wherever she could see it. She was a very vocal advocate for minorities, the poor, AIDS patients, women’s reproductive rights, and gay, lesbian, and transgender people. In 1993 ze published the coming-of-age novel Stone Butch Blues which encouraged conversation about ‘the complexity and fluidity of gender’ and won many awards.

“[Stone Butch Blues] changed trans history. It changed dyke history. And how it did that was by honestly telling a brutally real, beautifully vulnerable, and messy personal story of a butch lesbian.”

Leslie and Minnie, 1993 Copyright: Jonathan G. Silin.

Hir non-fiction book Transgender Warriors: Making History from Joan of Arc to Dennis Rodman, published in 1996, is considered to be ‘one of the first books to articulate a trans-historical understanding of transgender identity and argue for the inclusion of gender nonconforming people throughout history.’

In 2011, she married her long-time partner - educator, activist, and essayist Minnie Bruce Pratt. Sadly though, Leslie died, aged 65, just three years later from complications of multiple tick-borne infections that she’d been suffering with since the 70s. Hir last words were:

“Remember me as a revolutionary communist.”

Researched and written by Katelyn Hanna.

Sources:

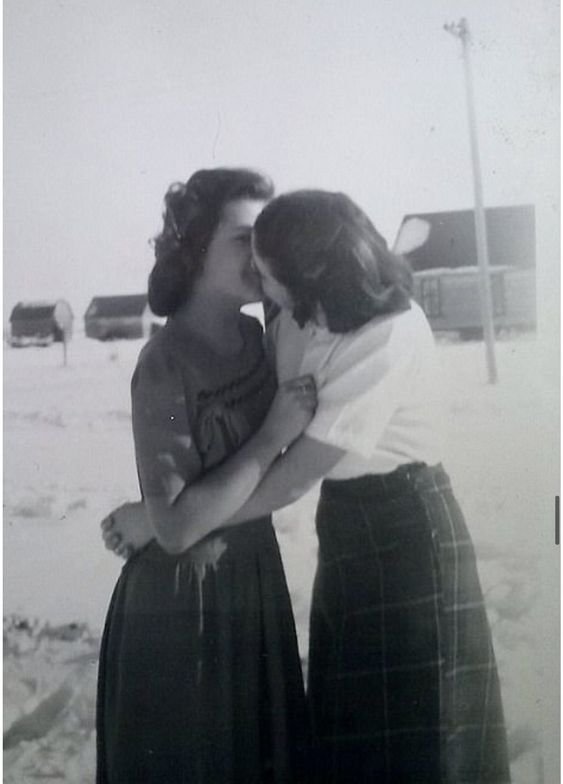

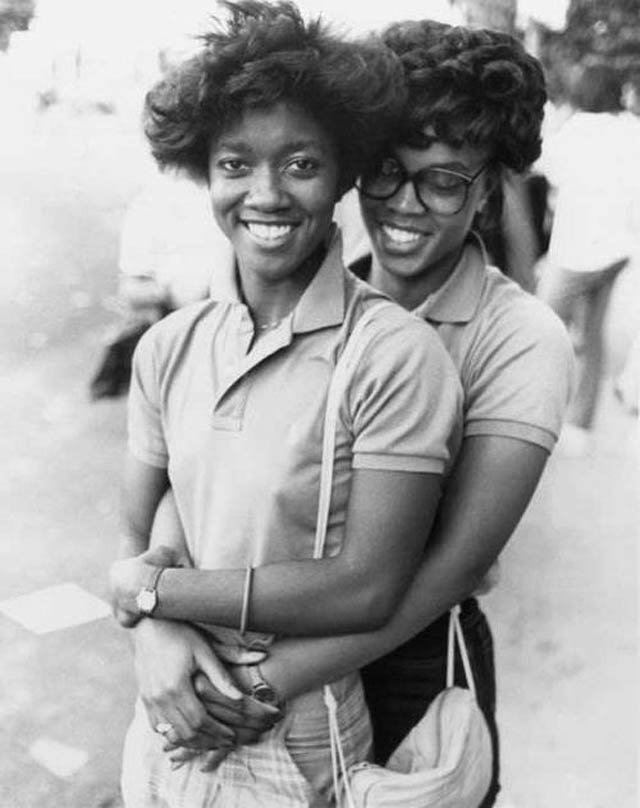

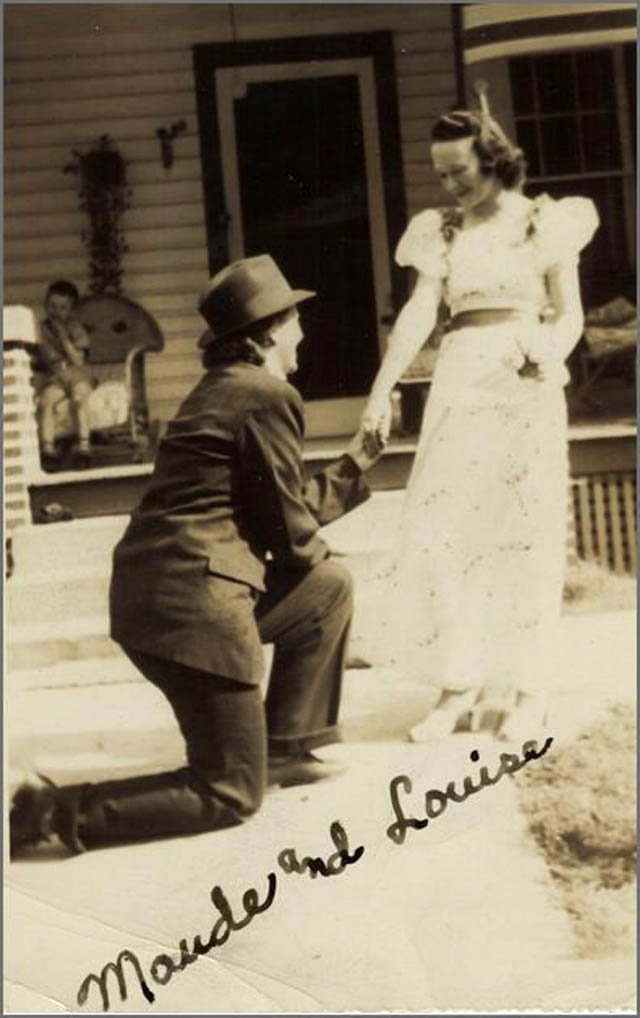

Vintage photos, ‘Vintage LGBT – Adorable Photographs of Lesbian Couples in the Past That Make You Always Believe in Love,’ online at: https://www.vintag.es/2016/05/vintage-lgbt-adorable-photographs-of.html [accessed 12 Mar. 2022].

Sappho’s poem translated by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, online at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/50343/one-girl#:~:text=Translated%20by%20Dante%20Gabriel%20Rossetti,could%20get%20it%20till%20now [accessed 12 Mar 2022].

Mark, Joshua J., ‘Sappho of Lesbos,’ online at: https://www.worldhistory.org/Sappho_of_Lesbos/ [accessed 11 Mar. 2022].

Medhurst, Eleanor, ‘Depicting Sappho: The Creation of the Original Lesbian Look,’ online at: https://dressingdykes.com/2021/03/19/depicting-sappho-the-creation-of-the-original-lesbian-look/ [accessed 11 Mar. 2022].

Coyle, Eugene, ‘LIFESTYLES: THE IRISH LADIES OF LLANGOLLEN: 'the two most celebrated virgins in Europe’ in History Ireland, Vol. 23, No. 6 (NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2015), pp. 18-20, Wordwell Ltd.

Wills, Matthew, ‘Who Were the Ladies of Llangollen?’ online at: https://daily.jstor.org/who-were-the-ladies-of-llangollen/ [accessed 11 Mar. 2022].

Giffney, Noreen, ‘Pride month DIB entry: the ‘Ladies of Llangollen,’ online at: https://www.ria.ie/news/dictionary-irish-biography/pride-month-dib-entry-ladies-llangollen [accessed 11 Mar. 2022].

National Library of Wales, Ladies of Llangollen: letters and journals of Lady Eleanor Butler (1739–1829) and Sarah Ponsonby (1751–1831) (microfilm, 1997).

Brideoake, Fiona, ‘“Extraordinary Female Affection”: The Ladies of Llangollen and the Endurance of Queer Community,’ Romanticism on the Net (36–37), 2004.

Woods, Rebecca, ‘The Life and Loves of Anne Lister,’ online at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-sh/the_life_and_loves_of_anne_lister [accessed 12 Mar. 2022].

Katz, Brigit, ‘The 19th-Century Lesbian Landowner Who Set Out to Find a Wife,’ online at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/19th-century-lesbian-landowner-who-set-out-find-wife-180971995/ [accessed 12 Mar. 2022].

‘An introduction to Anne Lister (1791-1840),’ online at: https://museums.calderdale.gov.uk/famous-figures/anne-lister [accessed 12 Mar. 2022].

Figes, Lydia, ‘Lesbian love and coded diaries: the remarkable story of Anne Lister,’ online at: https://artuk.org/discover/stories/lesbian-love-and-coded-diaries-the-remarkable-story-of-anne-lister# [12 Mar. 2022].

Booth, Francis, ‘Glimpses into the Secret Diaries of Anne Lister (“Gentleman Jack”),’ online at: https://www.literaryladiesguide.com/literary-musings/secret-diaries-anne-lister-gentleman-jack/ [accessed 12 Mar. 2022].

Rosenthal, Michele, ‘LUCY HICKS ANDERSON 1886TO –1954,’ online at: https://www.queerportraits.com/bio/anderson [accessed 14 Mar. 2022].

Keehnen, Owen, ‘Lucy Hicks Anderson – Nominee,’ online at: https://legacyprojectchicago.org/person/lucy-hicks-anderson [accessed 14 Mar. 2022].

Anita Sarkeesian, Ebony Adams, History vs Women: The Defiant Lives that They Don't Want You to Know, page 31.

Ballard, Dr Finn, ‘On This Day | 6 May 1933: Dorchen Richter Killed In Hirschfeld Institute Attack,’ online at: https://berlinguidesassociation.com/on-this-day-6-may-1933-dorchen-richter-killed-in-hirschfeld-institute-attack/ [accessed 14 Mar. 2022].

Flourish, Clare, ‘DORA RICHTER,’ online at: https://clareflourish.wordpress.com/2020/07/30/dora-richter/ [accessed 14 Mar. 2022].

Neumann, Boaz, ‘The Nazis Tolerated Gays. Then Everything Changed,’ online at: https://www.haaretz.com/jewish/holocaust-remembrance-day/.premium.HIGHLIGHT.MAGAZINE-the-nazis-tolerated-gays-then-everything-changed-1.6869815 [accessed 14 Mar. 2022].

‘History of Homosexuality in Berlin,’ online at: https://www.visitberlin.de/en/history-homosexuality-berlin [accessed 14 Mar. 2022].

Leonidas Hill, ‘The Nazi Attack on 'Un-German' Literature, 1933-1945,’ in The Holocaust and the Book: Destruction and Preservation (2001).

Kaye, Hugh, ‘The incredible story of the first known trans woman to undergo gender confirmation surgery,’ online at: https://www.attitude.co.uk/article/the-incredible-story-of-the-first-known-trans-woman-to-undergo-gender-confirmation-surgery/26195/ [accessed 14 Mar. 2022].

Whisnant, Clayton J., ‘A Peek Inside Berlin's Queer Club Scene Before Hitler Destroyed It,’ online at: https://www.advocate.com/books/2016/7/19/peek-inside-berlins-queer-club-scene-hitler-destroyed-it [accessed 14 Mar. 2022].

‘Niece who was wilder than Wilde,’ online at: https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/niece-who-was-wilder-than-wilde-1.1105899 [accessed 12 Mar. 2022].

‘Wilde by name, Wilde by nature: The story of Oscar’s niece Dolly,’ online at: https://epicchq.com/story/wilde-by-name-wilde-by-nature-the-story-of-oscars-niece-dolly/ [accessed 12 Mar. 2022].

‘Dorothy Wilde,’ online at: https://worldqueerstory.org/2019/09/07/dorothy-wilde/ [accessed 12 Mar. 2022].

Field, Allyson Nadia, ‘Dorothy Arzner,’ online at: https://wfpp.columbia.edu/pioneer/ccp-dorothy-arzner/ [accessed 13 Mar. 2022].

Barson, Michael, ‘Dorothy Arzner,’ online at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Dorothy-Arzner [accessed 13 Mar. 2022].

Kay, Karyn, and Gerald Peary, ‘Interview with Dorothy Arzner,’ (July 16, 2011).

Hutchinson, Pamela, ‘The pioneering filmmaker who broke the mould for women in Hollywood,’ online at: https://lwlies.com/articles/dorothy-arzner-dance-girl-dance-female-director-hollywood/ [accessed 13 Mar. 2022].

Higgins, Bill, ‘Hollywood Flashback: In 1929, a Woman Directed Paramount’s First Talkie,’ online at: https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/hollywood-flashback-1929-a-woman-directed-paramounts-first-talkie-1063029/ [accessed 13 Mar. 2022].

UCLA Film and Television Archive

‘House Un-American Activities Committee,’ online at: https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/education/presidential-inquiries/house-un-american-activities-committee [accessed 24 Mar. 2022].

Madsen, Axel, The Sewing Circle: Hollywood's Greatest Secret, (1995).

Shibusawa, Naoko, ‘The Lavender Scare and Empire: Rethinking Cold War Antigay Politics,’ in Diplomatic History (2012).

Lipsky, Dr Bill, ‘Pat, Cleo, and Ernestine: Pioneering Black Members of the Daughters of Bilitis,’ online at: http://sfbaytimes.com/pat-cleo-and-ernestine-pioneering-black-members-of-the-daughters-of-bilitis/ [accessed 14 Mar. 2022].

Martin, Dell, ‘Pat Walker: 1938-1999,’ in Before Stonewall: Activists for Gay and Lesbian Rights in Historical Context (2002), pp 191-92.

Marcus, Eric and Gallo, Marcia, ‘Ernestine Eckstein,’ in Making Gay History: The Podcast, online at: https://makinggayhistory.com/podcast/ernestine-eckstein/ [accessed 14 Mar. 2022].

Brownworth, Victoria A., ‘Black History Month: Ernestine Eckstein,’ online at: https://epgn.com/2022/02/09/black-history-month-ernestine-eckstein/ [accessed 14 Mar. 2022].

Ernestine Eckstein Interview in The Ladder: A Lesbian Review, June 1966, pg. 10.

Katz, Jonathan, Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A. (New York, 1976).

‘Life Story: Marsha P. Johnson (1945-1992),’ online at: https://wams.nyhistory.org/growth-and-turmoil/growing-tensions/marsha-p-johnson/ [accessed 15 Mar. 2022].

Keehnen, Owen, ‘Marsha P. Johnson – Inductee,’ online at: https://legacyprojectchicago.org/person/marsha-p-johnson [accessed 15 Mar. 2022].

Coke, Hope, ‘The inspiring life of activist and drag queen Marsha P. Johnson,’ online at: https://www.tatler.com/article/who-is-marsha-p-johnson-drag-queen-gay-activist [accessed 15 Mar. 2022].

Trotta, Daniel, ‘Forsaken transgender pioneers recognized 50 years after Stonewall,’ online at: https://graphics.reuters.com/USA-LGBT-STONEWALL/010092NF3GR/index.html [accessed 15 Mar. 2022].

Interview with Marsha P. Johnson in The Stonewall Reader (2019) pp 135-140.

Interview with Sylvia Rivera in The Stonewall Reader (2019) pp 141-147.

Weber, Bruce, ‘Leslie Feinberg, Writer and Transgender Activist, Dies at 65,’ online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/25/nyregion/leslie-feinberg-writer-and-transgender-activist-dies-at-65.html [accessed 22 Mar. 2022].

Pengelly, Martin, ‘Leslie Feinberg, Stone Butch Blues author and transgender campaigner, dies at 65,’ online at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/nov/17/leslie-feinberg-author-transgender-campaigner-dies-65 [accessed 22 Mar. 2022].

Feinberg, Leslie, ‘Stone Butch Blues,’ online at: https://www.lesliefeinberg.net/ [accessed 22 Mar. 2022].

Keehnen, Owen, ‘Leslie Feinberg – Nominee,’ online at: https://legacyprojectchicago.org/person/leslie-feinberg [accessed 22 Mar. 2022].

Falk, Misha, ‘Trans activism isn’t just about pronouns and bathrooms. It’s about class struggle,’ online at: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/oureconomy/trans-activism-isnt-just-about-pronouns-and-bathrooms-its-about-class-struggle/ [accessed 22 Mar. 2022].

Frey, Kate, ‘Leslie Feinberg: Transgender Warrior,’ online at: https://www.socialistalternative.org/2015/01/09/leslie-feinberg-transgender-warrior-2/ [accessed 22 Mar. 2022].

Pratt, Minnie Bruce, ‘Leslie Feinberg – A communist who revolutionized transgender rights,’ 2014.

Tyroler, Jamie, ‘Transmissions – Interview with Leslie Feinberg,’ 2006.