By Ai Chaobang

On the extreme edge of an Asian peninsula called Europe, in a small archipelago, two island nations drift side by side.

Their stories share a basic structure. Both were written by many different peoples who arrived from elsewhere over thousands of years. From both too did many people leave, adding their hands to the stories of peoples far away.

Immigration and emigration have been the building blocks of the Irish story. At times these movements have involved terrible pain – uninvited colonial aggressors in, fugitives from catastrophe out. Yet from the effort to build a nationhood comfortable with its nature as “the people from somewhere else” has emerged an Irish modernity enriched on the contributions of immigrants, and whose diaspora enriches the world in turn.

Immigration and emigration have also been the building blocks of the English story. Alas, that there is a nation which never came to terms with its nature, instead retreating behind an imagined paradoxical fortress: the “island country”. In inventing race, abusing the very immigrants who kept coming to build it, and otherising most of the known world through the imperialist violence of its emigrants, its own modernity is made brittle and now stands on the brink of collapse.

Humans are migrants. All societies are either wholly or partly built upon migration; no people and no peoples, if they go back far enough, originate from where they stand now. To be human is to have a story, and thereby a journey – a journey which, even if it does not go far, makes meaning out of its intersections with the journeys of others. Every people in the world, then, is to some extent like the Irish and the English: that is, defined by movements in and movements out, of people, of things, of ideas, with all the challenges and opportunities of how to write them into your story for the better. Ethnicity is imaginary. There is no homogenous society, no monolithic culture.

Every journey is unique. Every person is unique. Diversity is the first fact of what it means to be human – but so too, first equal, is common humanity. All categories of people, all notions of in-groups and out-groups – of gender, of race, of class and so forth – are in the first instance meaningless. They have only the meanings to which we most often in error have given them, for we all have more in common than in contrast. We each have a journey; we each deserve to live in a love-based world as sovereigns of our own bodies; and we all hurt when we bleed.

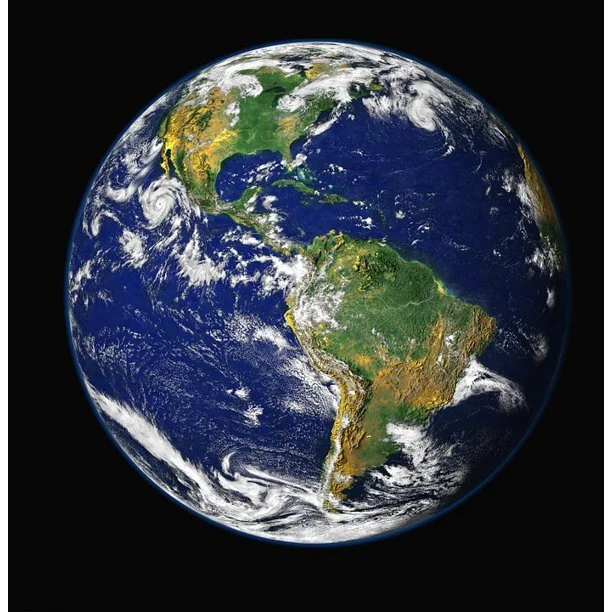

The story of humanity together is a story of migration. Our emergence from Africa; our long journeys into Europe, Asia and across to the Americas; our great voyages along the Silk Road and upon the Indian Ocean trade routes; the migrations of the Austronesian peoples across the Pacific, the Vikings across the Atlantic, the peoples of the steppes into Europe, the Bedouin across North Africa; and alas, more problematic movements like the Mongol conquests and the reach of the European colonial empires. For better and for worse, every aspect of the world in which we live today is built upon migration. So it will always be – and the task of making it work well for everyone falls to us all.

Our minds travel where our feet cannot. Even sitting in one spot, in a living room or a library, a train carriage or a prison cell, we grow ourselves by journeying far away through books, films, video games, the internet or our imaginations alone. As humans we imagine our realities. Nations, religions, companies, even our favourite sports teams – these exist first and foremost only in our minds, such that to participate in them is to cast our imaginations on journeys of unification with millions of other participants we will never physically meet.

As a wise poet once said, Everything passes on and everything remains,/ but our lot is to pass on,/ to go on making paths,/ paths across the sea. Across the sea – and across worlds. In every land, in every individual, a universe; and all universes are connected.

So it has been, so it will be, and so it is now in a globalised world facing climatic, ecological and socio-political calamity. A world, that is, where these same existential challenges loom upon us all, and make plain more than ever in history our shared humanity. From climate change to mass extinctions, from authoritarianism and prejudice to COVID-19 – these are universal menaces which cross all walls, and so must we if we are to prevail over their common threat to the future of our kind.

In a world with an unhealthy fixation with walls, to cross from world to world brings great vulnerability. It is to be the eternal other, wandering in a liminal space that touches multiple worlds at once but is never sufficiently of them to belong to any. In liminality there is danger, alienation and pain – but also incredible power. You belong in no world, but can draw on your experiences of them all. To walk in this liminal space is to become conscious of the water of which the fish knows nothing; to see for what they are the mere shadows which those chained in Plato’s cave insist are absolute reality. The perspective of the liminal outsider offers wisdom that no-one else can; sees the strengths and weaknesses of any one society in the bigger picture of them all. By sharing it, it can enable that society to improve as a home for us all – enable a world in which we all belong.

We cross worlds. We push down walls so that they become bridges. There is no possible future in which we do not.

Discover more of Chaobang’s enlightened writing

You can listen to Chaobang narrate his essay in the video below.