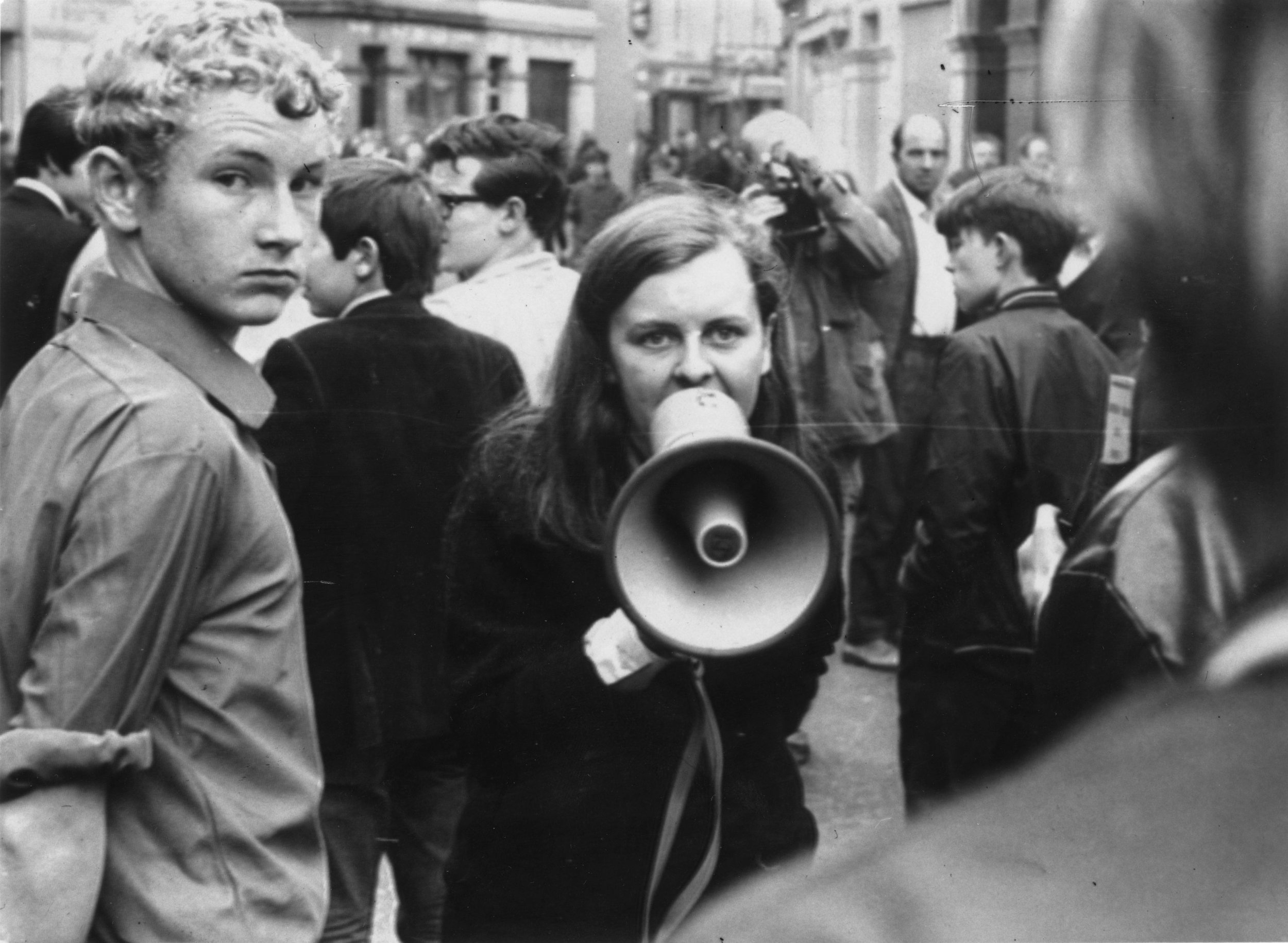

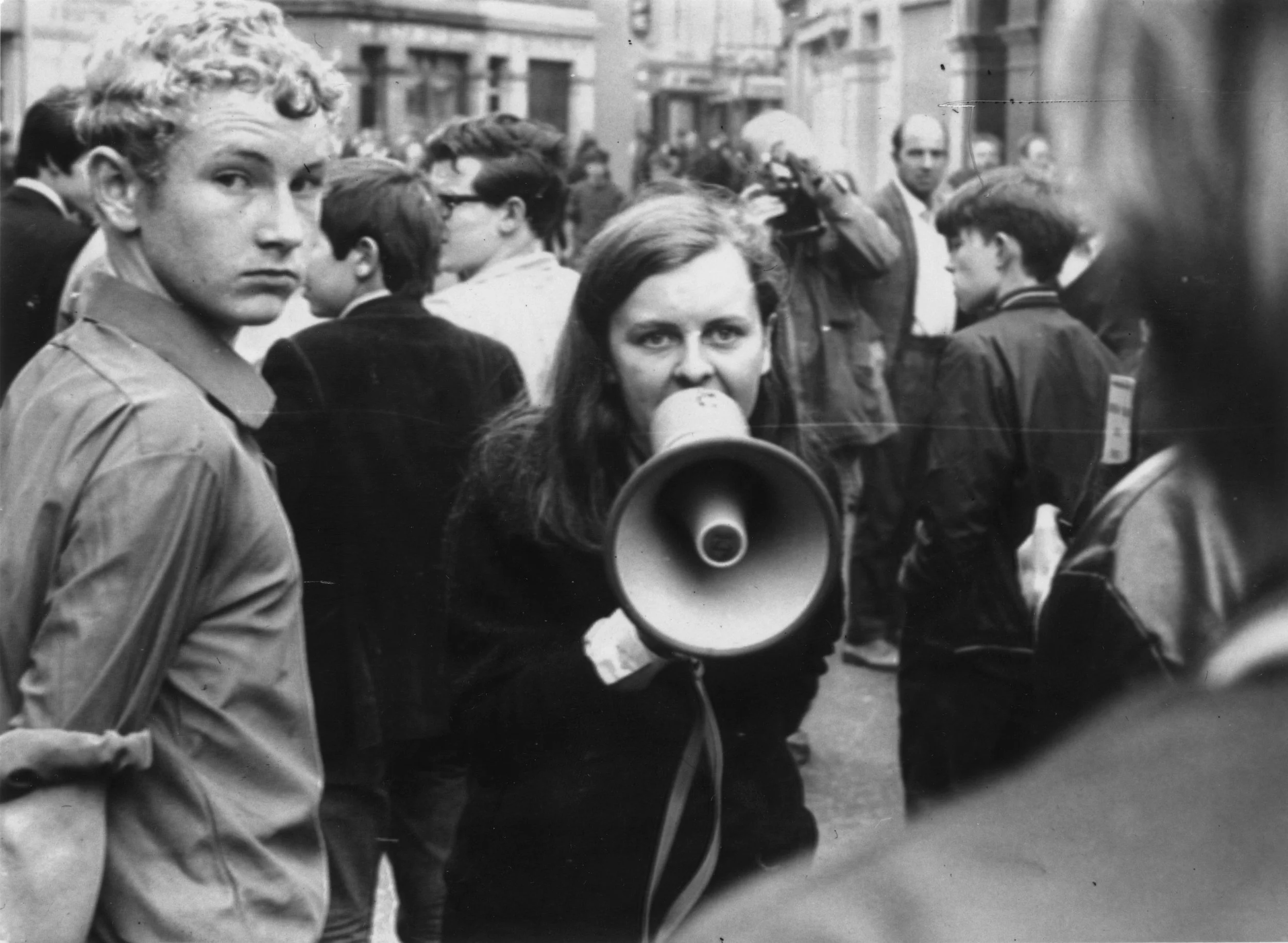

Bernadette Devlin McAliskey

Civil Rights Leader / Former MP (1969-74)

Credit: An Sionnach Fionn

Born in Tyrone in 1947, Bernadette McAliskey (nee Devlin) grew up in a working-class family of six children. Before he died when she was nine, her father taught her about Irish political history which, among other things, would influence her trajectory in life. The conditions in which the family lived following his death, with her mother dependent on welfare for support, made her a socialist in her beliefs. Bernadette was still only a teenager when her mother also died, leaving her to help raise her younger siblings while she attended college.

‘I come from a long line of strong women. My mother and grandmother were both widows. The level of poverty that I grew up in brings a degree of strength and creativity to women, because they have to manage.’

At Queens University Belfast, Bernadette became active in politics and on 9 October 1968 she co-founded the People’s Democracy - a ‘non-partisan, non-political organisation based on the simple belief that everyone should have the right to a decent life.’ It was founded in reaction to the 5 October civil rights march in Derry which was broken up after RUC baton-charged the peaceful protestors. The People’s Democracy held sit-ins and marches demanding equality for all, and Bernadette became a competent and notable speaker.

Following a by-election in April 1969, Bernadette was elected to Westminster and at age 21, remained the youngest woman ever elected to Westminster until that record was broken in 2015.

After taking part in the ‘Battle of the Bogside’ in August 1969 – a three-day riot in which Catholic residents rose up against the discrimination of the RUC – Bernadette travelled to the US. Here, she met with members of the Black Panther Party – a Marxist-Leninist black power political organisation – and gave them her support. Later, when she was awarded the key to the city of New York before returning to Northern Ireland, she gave it to a representative of the Black Panthers.

‘… ‘My people’ – the people who knew about oppression, discrimination, prejudice, poverty and the frustration and despair that they produce – were not Irish Americans. They were black, Puerto Ricans, Chicanos…’

Credit: Getty Images

Once home, she was convicted, in December, of incitement to riot in relation to the Battle of the Bogside and served a few months in jail. She also faced harsh criticism and sexism from all angles.

‘I find it difficult to take […] Bernadette Devlin seriously. A leader of civil rights for Irish Catholics should first be conformed with the spiritual moral teachings of the Catholic Church. Mini-skirted Bernadette Devlin conforms to and gives strength to the popular fashions of a godless world.’ – Irish-American contributor to Belfast Telegraph, 1970

‘We are just sick at what we saw on television – our brave police being attacked by a lot of hooligans! […] We saw Devlin and ‘her people’ in their true colours last night. These people should just sit back for a few minutes and thank God that they are living in Ulster. If they were living anywhere else they would be dead from starvation…’ - ‘Five working housewives’, contributor to the Belfast Telegraph, 1969 following the Battle of the Bogside

Credit: ThoughtCo

In 1972, Bernadette lay witness to the Bloody Sunday massacre in Derry in which 14 people were shot dead during an internment protest. In the House of Commons later Bernadette was denied the right to speak - despite there being a parliamentary convention that said that any Member of Parliament witnessing an incident under discussion would be granted an opportunity to speak about it. When the Home Secretary, Reginald Maudling, then incorrectly said that the British paratroopers had fired on civilians in self-defence, Bernadette crossed the floor and slapped him. ‘[Bloody Sunday] was when the civil rights movement ended and the armed struggle began,’ she said later, ‘That was the point of realisation for me that the penalty for demanding equal rights in your society was that your government would kill you.’

Over the next number of years Bernadette helped to establish the Irish Republican Socialist Party (IRSP) before joining the Independent Socialist Party. She also supported the prisoners on the blanket protest and dirty protest at Long Kesh prison and eventually, the hunger strikers in the early 1980s.

In 1981, Bernadette and her husband were both shot multiple times in front of their children in their home in Tyrone by the Ulster Freedom Fighters, a cover name of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA). Even though British soldiers had been outside watching the home, they failed to stop the gunmen from entering.

Credit: Hozier

After this, Bernadette began to campaign locally and work with women in her estate. In 1997, she co-founded STEP (South Tyrone Empowerment Programme) to research and campaign across many areas such as housing, legal rights, water charges etc. More recently, her work has involved trying to help migrant workers in the community.

‘I am doing the same thing I have always done. It's still about people having a right to fulfil their potential and not be excluded from that because of other people's prejudice.’

Sources:

Moreton, Cole, ‘Bernadette McAliskey: Return of the Roaring Girl,’ online at: https://web.archive.org/web/20081211164929/http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/profiles/bernadette-mcaliskey-return-of-the-roaring-girl-951825.html [accessed 8 July 2022].

Belfast Telegraph, 13 July 1970.

Belfast Telegraph, 15 Aug. 1969.

Lewis, Jone Johnson, ‘Bernadette Devlin Profile,’ online at: https://www.thoughtco.com/bernadette-devlin-biography-3530416 [accessed 8 July 2022].

‘Bernadette Devlin,’ on A Century of Women, online at: https://www.acenturyofwomen.com/bernadette-devlin/ [accessed 7 July 2022].

‘BERNADETTE MCALISKEY,’ online at: https://hozier.com/activitsts/bernadette-devlin/ [accessed 6 June 2022].

‘BERNADETTE DEVLIN’S MAIDEN SPEECH TO PARLIAMENT (1969),’ online at: https://alphahistory.com/northernireland/bernadette-devlins-maiden-speech-parliament-1969/ [accessed 8 July 2022].