© National Museums NI

Published: 10th February 2020

Making Her Mark, an exhibition at the Ulster Museum, recognises the impact of women artists on the history of printmaking. It explores how they used the art form to expand their practice, gain financial independence and bring their art to a wider public. The exhibition opened in October 2018 and closed 20th October 2019. https://www.nmni.com/whats-on/making-her-mark

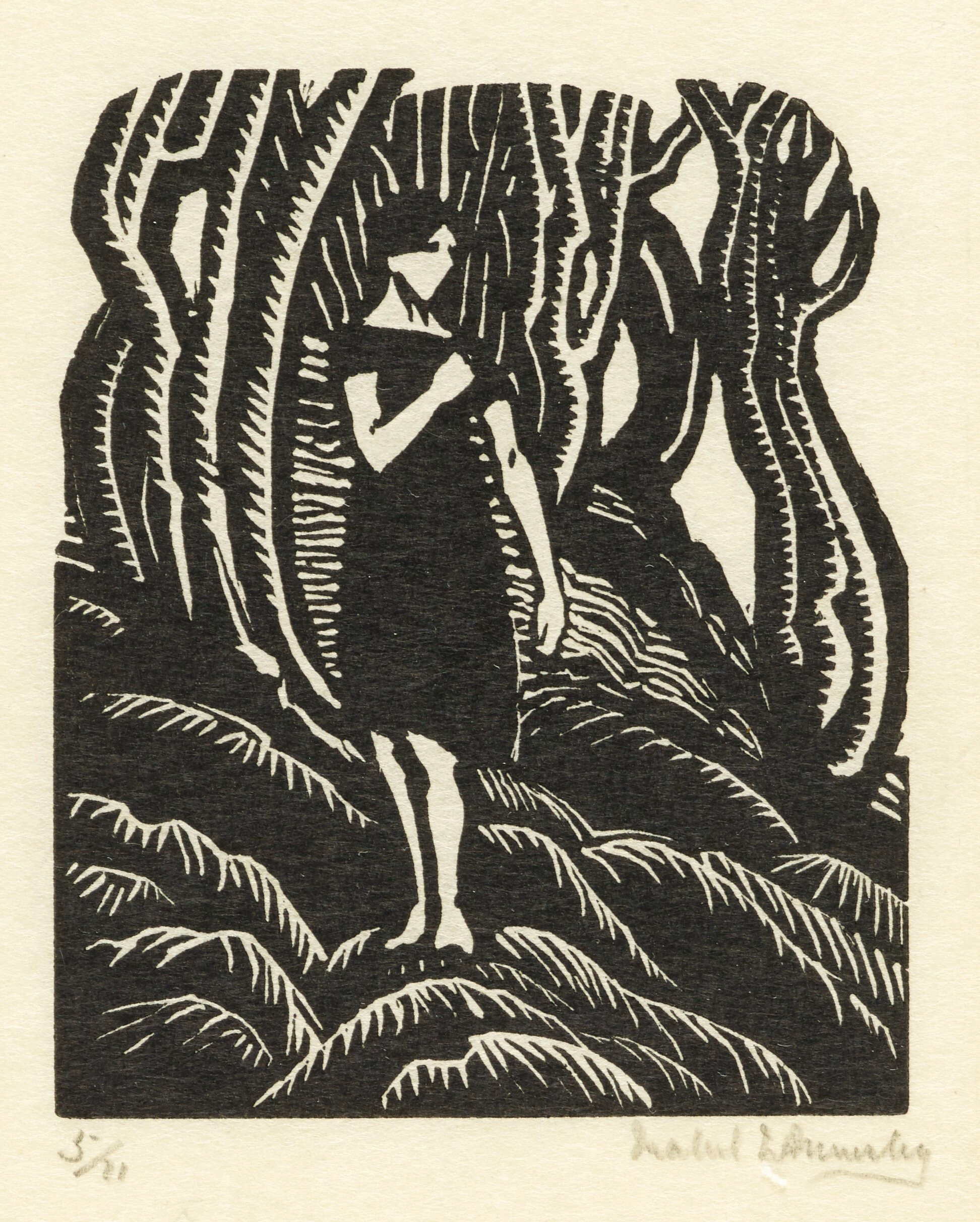

Lady Mabel Annesley (1881–1959) The Lake (Frontispiece to County Down Songs) c. 1925 Wood-engraving BELUM. Pt93 © With the kind permission of the descendants of Lady Mabel Annesley

The exhibition includes 22 women artists covering nearly 200 years of print making; working across wood-engraving, lithograph, etching and screen-print. Some worked exclusively in the practice, many used the technique to promote women’s liberation and social issues and others simply used it as another means of expression. There are multiple Irish women in the exhibition, or artists who had a connection to Ireland.

Lady Mabel Annesley (1881-1959) I’m O’er Young (illustration for Robert Burns’ Poems) c. 1925. Wood-engraving BELUM.Pt86 © With the kind permission of the descendants of Lady Mabel Annesley

Lady Mabel Annesley (1881-1959) was at the centre of the wood-engraving revival of the 1920s and 30s in Ireland. As well as practising herself, she championed her fellow wood-engravers. We can thank Annesley for many of the works in this exhibition; she gifted 100 wood-engravings to what is now the Ulster Museum in 1939.

Lady Mabel Annesley (1881–1959) Flax Dam c. 1939 Wood-engraving BELUM.Pt92 © With the kind permission of the descendants of Lady Mabel Annesley

Annesley grew up in County Down on her family’s Castlewellan estate, which she inherited at thirty-three and saved from financial disaster. A keen artist from an early age, she trained at the Frank Calderon School of Animal Painting. Following her husband’s death in 1913, she studied wood-engraving under Noel Rooke at the Central School of Arts and Crafts.

Lady Mabel Annesley (1881–1959) Yon’s the Rare Jewl o’ a Wee Pig (Tailpiece for Apollo in Mourne) c. 1926. Wood-engraving BELUM.Pt390 © With the kind permission of the descendants of Lady Mabel Annesley

Despite being a member of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy, the land and the working life of the Mourne Mountains was central to her work. As well as making many engravings of the area she illustrated books on local traditions including Richard Rowley’s Apollo in Mourne and County Down Songs.

Doris Violet Blair (active 1940 -1980) Interior c. 1940 Etching BELUM.Pt232 © Estate of Doris Violet Blair

Doris Violet Blair (active 1940 -1980) is known for her work as an official war artist during the Second World War, recording women’s impact on the war effort in Belfast. This domestic scene, created during wartime, reminds us that while women took on more responsibility during the war they were often still expected to continue to be homemakers.

Margaret Clarke (1884 -1961) Irish Free State butter, eggs and bacon for our breakfasts (Commissioned by Empire Marketing Board (1926-1933) and printed for HM Stationery Office by Waterlow & Sons) c. 1930 Lithographic poster BELUM.Pt828 © Estate of Margaret Clarke

Margaret Clarke (1888 -1961) was the second woman to be elected as full academician to the Royal Hibernian Academy and received many awards, commissions and exhibitions. One of her most important commissions was for the Empire Marketing Board. Clarke’s posters were displayed in English towns to promote the idea that buying goods from Ireland further encouraged the Irish to buy from Britain.

Kate Greenaway (1846 -1901) Girl Spinning while a Fairy Appears on a Dove c. 1875 Ink drawing BELUM.U1194 © National Museums NI

Kate Greenaway (1846-1901) was inspired by characters she met growing up in London and these faces appear in her work as an adult. She started by designing Christmas and New Year cards, going on to illustrate books and eventually writing and illustrating her own in the 1870s. Her cards were the most successful designs sold by Northern Irish printing firm Marcus Ward.

Elizabeth Rivers (1903 -1964) Winter Skies 1960 Wood engraving BELUM.Pt762 © Estate of Elizabeth Rivers

English-born Elizabeth Rivers (1903 -1964) first came to Ireland in 1935, eventually settling here permanently. She exhibited widely throughout the 1940s and 1950s and was central to the rise of Modernism in Ireland. One of her most successful publications, Stranger in Aran, which described her time living on the island, was published by Cuala Press (a later development of Dun Emer Press).

Elizabeth Rivers (1903 -1964) Saint Alone Mid 1900s Wood-engraving BELUM.Pt858 © Estate of Elizabeth Rivers

Rivers saw the disruption and violence of the Second World War echoed in Christopher Smart’s Rejoice in the Lamb, which he wrote when in Bedlam psychiatric hospital between 1756 and 1763. She used his manuscript to give titles to her engravings in one of her most famous works Out of Bedlam.

The niece of Lily Yeats, of Dun Emer Press, it is fitting that Anne Yeats (1919 - 2001) turned to print later in her career. She was a founding member, with Elizabeth Rivers, of the Graphic Studio Dublin, set up in 1960 to teach traditional printmaking skills and support artists. The studio is considered to have been at the forefront of Irish printmaking and gave Ireland an international reputation for the art.

Lady Elizabeth Thompson Butler (1846 -1933) A Despatch-Bearer, Egyptian Camel Corps 1888 Lithographic Poster BELUM.Pt1132© National Museums NI

Lady Elizabeth Thompson Butler (1846 -1933) produced this print for The Graphic, a magazine associated with social and political reform, where Butler was a staff artist. Despite their titles and her husband, Sir William Francis Butler’s, rank in the military, they were both anti-imperialist and outspoken about the treatment of the Irish people during the famine, which Sir Butler witnessed as a child.

Ann Bailey (active 20th Century) Quai d’Anjou, Paris Early 1900s Etching BELUM.Pt500

Very little is known about this work, or the artist – only that this etching was once exhibited at the Belfast School of Art, where Ann Bailey (active 20th Century) may have studied. While lack of information can be an issue with any artist, it is women artists who most frequently become ‘invisible’ in art history. Although in the last two hundred years over thirty percent of professional artists have been women, historically they have been excluded from academy and gallery systems, leading to their work being less often recorded and written about. When no information can be found on an artist it may mean that they did not pursue an artistic career. Throughout the 1800s and 1900s, as education opened up for women, many from privileged backgrounds attended classes, creating art for themselves and their friends.

Agnes Miller Parker (1895 -1980) The Challenge 1934 Wood-engraving BELUM.Pt13 © Estate of Agnes Miller Parker

For any further information please contact anna.liesching@nmni.com

Thanks to Anna Liesching of the Ulster Museum, the National Museums NI, and the copyright holders of the above images, for facilitating this photo essay.