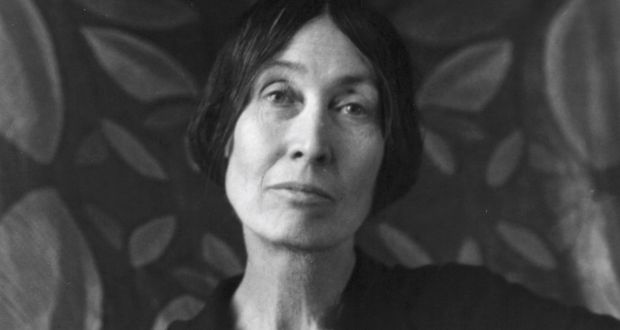

Image Source: Wikipedia

Amy ‘Amma’ Carmichael,1867–1951

Missionary

Amy Carmichael was born into a prosperous, middle-class Ulster Presbyterian family, but when her father died in 1885, her education came to an abrupt halt. From an early age she was involved in holding Bible meetings for children, and organised classes for ‘shawlies’, the mill-girls of Belfast. These were so successful that as a result, The Welcome hall, built by donations, opened in January 1889.

Amy and her mother were invited to continue their charitable work in Manchester in 1889, but this was cut short due to Amy’s ill-health. Later,she recalled: ‘I was deep in slums when I was 17. ’Amy was strongly influenced by the Quaker Robert Wilson, who she met in Belfast in 1887. They shared a commitment to religion and missionary work, and had an unusual relationship: she took the place of his deceased daughter, while Amy referred to him as ‘Fatherie’. She lived at his home in Cumberland, helping with his religious work, leading the weekly Scripture Union, and writing her first book, Bright Words.

Amy experienced a ‘call’ to missionary work, and in March 1893, she left with the Evangelistic Band to spend just over a year in Japan, where she struggled greatly to learn the language, but convinced her fellow missionaries to adopt traditional Japanese dress. She left Japan for Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) due to illness in July 1894, but quickly returned to England after receiving news that ‘Fatherie’ had had a stroke.

In spring 1895, she applied to the Church of England Zenana Missionary Society. Although not an Anglican, she was accepted, and sailed for India in October, taking leave of ‘Fatherie’ for the last time. She arrived in India suffering from dengue fever, but threw herself into studying Tamil. She formed her own group of mission sisters who spent seven years travelling around southern India before settling at Dohnavur, where Amy would remain for the next six decades.

At Dohnavur, she established a Christian community focused on reforming the Hindu practice of devadasis, the ceremonial marriage of young girls to a temple deity. After forty years, the community had 800 residents, served by nurseries, schools, a hospital, and a house of prayer. It was modelled on a familial structure, and missionaries contributed to teaching, nursing, engineering and farming. She insisted that Dohnavur workers should not expect a salary since the organisation never actively fund-raised.

Amy’s ideal was that ‘Indian and European, men and women, live and work together [...] each contributing what each has for the help of all.’ She expressed some sensitivity to Hindu traditions, but occasionally paternalistically attempted to control the lives of adult residents and workers. She avoided providing sex education to the young people in her care, seemingly in an attempt to prevent ‘arousal’. For Carmichael, no material improvement in living conditions was worth having if not attended by Christianity.

Amy published 38 books, mostly relating to Dohnavur, many of which were translated into other languages. She was unconventional, passionately committed to her work, and wore Indian dress. In 1919, she was awarded the Kaisar-i-Hind Medal for Public Service in India. Devadasis was finally outlawed with the passage of a 1947 act by the Madras state parliament. The work at Dohnavur continues, however, to protect vulnerable children. Today, all fellowship members are Indian nationals, and the hospital treats patients of all faiths and classes.

Sources: Elisabeth Elliot, A Chance to Die:The Life and Legacy of Amy Carmichael (Fleming H. Revell, 1987);Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online edition; Margaret Wilkinson, I Remember Amy Carmichael ([for the author],1996); Amy Carmichael,The Widow of the Jewels( [1928] SPCK, 1950)

Research by Dr Angela Byrne, DFAT Historian-in-Residence at EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum. Featured in the exhibition 'Blazing a Trail: Lives and Legacies of Irish Diaspora Women', a collaboration between Herstory, EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.