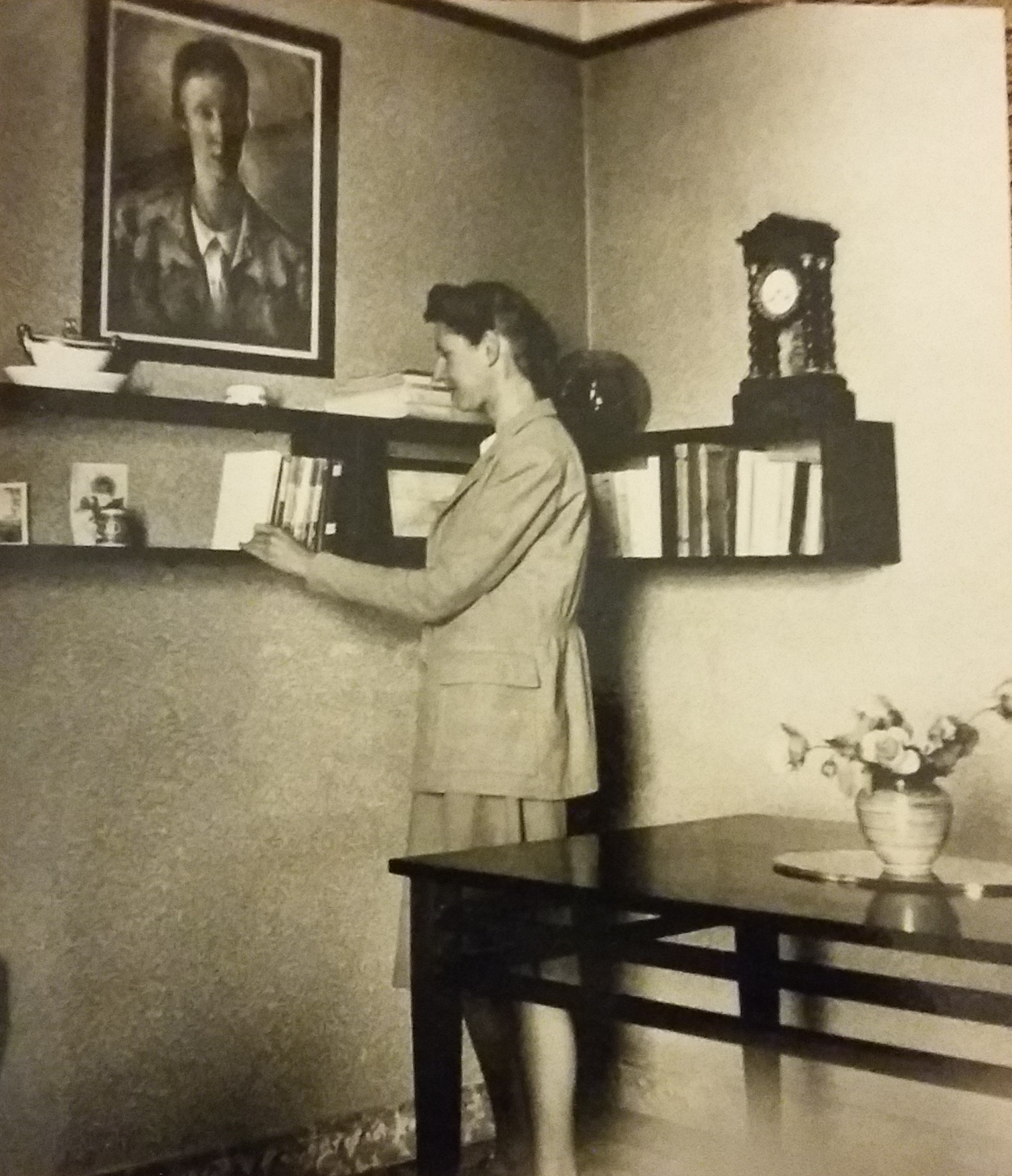

Aleen Isabel Cust, 1868–1937

First woman veterinary surgeon in Britain and Ireland

Aleen Cust was the daughter of a baronet, but a life of ease was not for her. When her father died in 1878, her new guardians–also aristocrats–encouraged her independent streak, and supported her decision to become a veterinary surgeon, despite her mother’s disapproval.

In 1894, enabled by a modest private income, she enrolled in the New Veterinary College, Edinburgh aged 26. She was an excellent student, coming top of her class in her first year. She completed her training in 1900, but was barred by gender from using the title ‘veterinary surgeon’. The Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS) maintained that in their regulations, the word ‘student’ implied male student. She had excellent references, however, and was offered a position as assistant to William Byrne’s veterinary practice in Athleague, Co. Roscommon.

As Byrne’s assistant, Cust gained the respect of the people of Roscommon and east Galway. In 1905,when a vacancy arose for the position of veterinary inspector for Mountbellew District, she was elected by 14 council votes to 10, against two male candidates. Her appointment was contested by the Department of Agriculture on the basis that a woman could not be a member of the RCVS and therefore, she did not meet the requirements of the position. Galway County Council argued that no other trained and experienced veterinarian lived in the region, and in June 1906, her appointment was finally sanctioned by the Department.

Cust was hardworking and determined, but still needed the support of male allies who fought on her behalf. On the evening of her selection, Councillor J.C. McDonnell said, in response to the question of her qualifications, that the RCVS ‘would have to change their opinion and adopt later day ideas (hear hear).’ Despite these noble sentiments on the injustice of Cust’s disbarment from the RCVS, the irony went unremarked that they were 24 men voting on the professional fate of a woman. Not everyone agreed on ‘later day ideas’. The Western News editorialised: ‘The county council have made an appointment in the horse and brute kingdom which appears to us at least disgusting, if not absolutely indecent ... We can understand women educating themselves to tend women–but horses! Heavens!’

William Byrne died in 1910, and Cust took over his practice. In 1915, she took a leave of absence from her Galway County Council and drove her own car to Abbeville, France, to volunteer as veterinary to the tens of thousands of horses on the Western Front. The passage of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act in 1919 forbade the exclusion of women from professions, and meant that the RCVS were now obliged to consider Cust’s membership. She was finally awarded her diploma in December 1922. From the 1920s, Cust found the Irish Free State no longer congenial, stating: ‘things became so unsettled that I had to leave. When one has the house raided and half a dozen revolvers are pointed at one’s head, it seems time to come home. But they were rather polite.’ She retired to the New Forest, England, where she devoted herself to breeding spaniels, but continued to attend Veterinary Medical Society meetings.

She died on 29 January 1937 while visiting friends in Jamaica, and was buried there. She left a fortune of almost £30,000, from which £5,000 was endowed for a scholarship in veterinary research (with a preference for female candidates), and £100 for a kennel at the RCVS in memory of her spaniels. An obituary published in The Times stated that Cust was ‘as much a pioneer in her particular sphere as, for example, Mrs Pankhurst, of women’s suffrage fame, was in hers, and the opposition encountered was as great in the one as it was in the other.’

Sources:Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online edition; Belfast News-Letter, 3 Feb. 1937;Western People, 23 June 1906;Western News, 4 Nov. 1905;Irish Times, 5 Feb. 2018;Skibbereen Eagle, 27 Feb. 1915;Freeman’s Journal, 22 Dec. 1922;The Times, 8 Feb. 1937;will of Aleen Cust, quoted in Irish Examiner, 19 Apr. 1937.

Research by Dr Angela Byrne, DFAT Historian-in-Residence at EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum. Featured in the exhibition 'Blazing a Trail: Lives and Legacies of Irish Diaspora Women', a collaboration between Herstory, EPIC The Irish Emigration Museum and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.