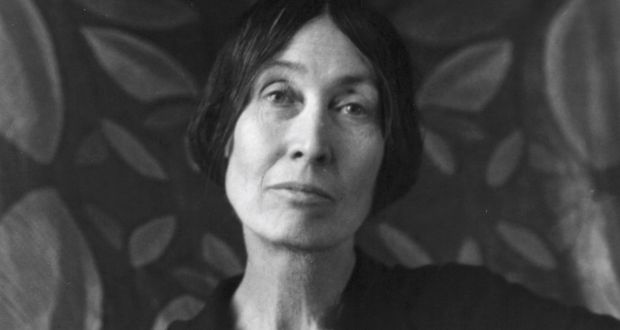

Edith Nesbit / Author / Poet

1858 - 1924

When Edith Nesbit was four years old, she lost her father, John Nesbit, to tuberculosis. Her mother, Sarah, twice widowed by her mid-forties, tried valiantly to run the progressive agricultural college in Kennington, London where her husband had been Principal. Overwhelmed and desperately concerned by the appearance of symptoms of tuberculosis in her second daughter, Mary, Sarah sold the college and, with it, Edith’s idylic childhood home.

During the decade that followed, Edith, Mary, her half sister, Saretta, and their mother, travelled through Britain and France in an effort to find a climate that would allow Mary to recover. Edith’s brothers, Alfred and Harry, were sent to boarding schools in England. This transient lifestyle disrupted her education woefully, although she learned to speak French proficiently and she never lost her passion for reading.

Bittersweet contentment was found after Mary died, aged just twenty, and Sarah took her remaining children to live in the tranquil Kent village of Halstead. Edith was fourteen by then and had ambitions to be a poet. She celebrated the lush beauty of the Kent countryside in the hundreds of poems, stories and novels she wrote during her lifetime. In her late teens, she moved to London with her mother but she returned to the countryside, which she missed desperately, as often as she could. Aged twenty-one and seven months pregnant, Edith married the flamboyant but serially unfaithful Hubert Bland. Both took lovers throughout their marriage and Edith, a vibrant, beautiful woman, had romantic liaisons with several younger men. Poverty provoked resourcefulness and she kept her little household afloat by designing greeting cards and writing stories for children. It was this experience of hardship and a strong belief in social justice that drove Edith and Hubert to help found the Fabian Society, a reforming socialist organisation that exists to this day.

Edith’s talent and determination brought well-deserved rewards and she moved her growing family into increasingly larger rented homes in the south east of London. By the time she could afford to rent a beautiful, rambling house in Well Hall, Eltham, she was rearing three children of her own alongside two more born to her best friend, Alice, who was having an affair with Hubert. It was in Well Hall, where she spent 22 years surrounded by orchards, farmland, and beautiful gardens that Edith began to write the wonderful stories for children that became her literary legacy. Drawing on incidents from her own childhood and the lives of her children she wrote The Story of The Treasure Seekers, The Wouldbegoods, Five Children and It and many others, including her beloved classic The Railway Children. She also wrote poetry, novels for adults and chilling horror stories.

An extravagant, generous, gregarious woman, Edith threw lavish parties at Well Hall; her guests included H.G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw, Charlotte Perkins Gilman and other literary luminaries. She also organised parties and performances for the poor schoolchildren of Deptford, providing them with desperately needed toys, food and clothing. She was enormously successful for a time but wartime and the death of her husband, Hubert, coincided with a falling away of her popularity. Managing her vast house became increasingly difficult so she sold flowers, eggs and vegetables, and took in paying guests to make ends meet. In 1917, she married for a second time. Shortly afterwards, she and her new husband, a marine engineer named Tommy Tucker, moved to two refurbished army huts at St Mary’s Bay in Dymchurch in Kent. She died there in May 1924, her second husband and her children by her side.

To read more about E. Nesbit’;s extraordinary life look out for a copy of The Life and Loves of E Nesbit by Eleanor Fitzsimons (Duckworth, 2019). All are welcome to attend the launch in Hodges Figgis, Dawson Street, Dublin, on Thursday 10 October at 6pm

Thanks to Eleanor Fitzsimons for this herstory.